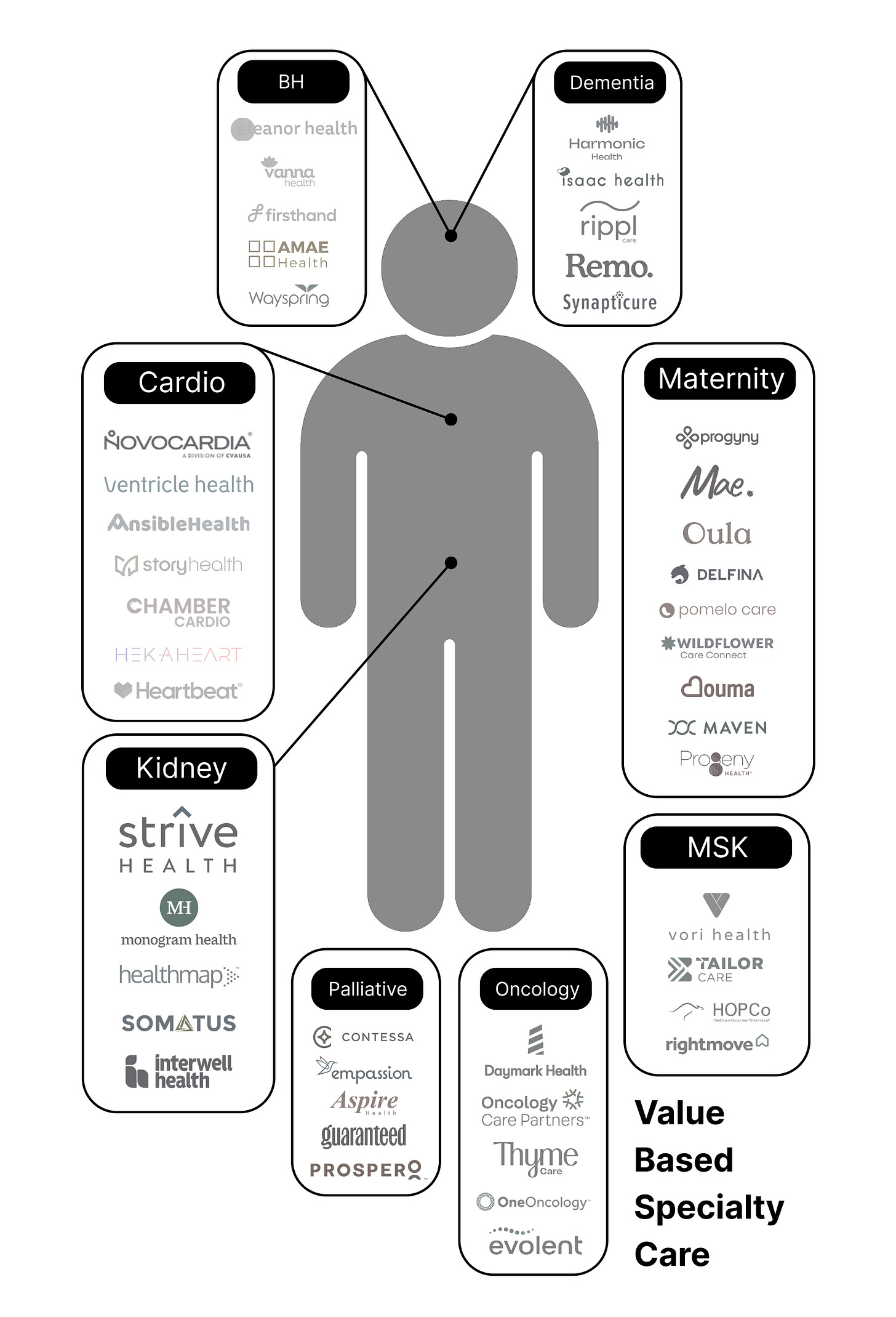

Value-based payment models have emerged across many specialties, but its potential varies widely by clinical and financial context. This piece focuses on three specialties: kidney care, cardiology, and behavioral health, where these contexts create strong conditions for success.

With over 160 specialties and sub-specialties in the US, there has been no shortage of venture-funded, value-based specialty care organizations over the last ten years. Examining these specialties, there are several factors that make for an attractive opportunity:

High-cost: If the specialty is costing insurers and patients a lot of money, there is more opportunity for savings.

Variable cost: If there’s a significant difference in the amount of money spent on different care pathways, there is more opportunity to reduce costs.

Variable quality: If there’s a significant difference in the quality of care and patient experience across different care pathways, there is more opportunity to improve quality.

Discrete condition: If the condition is clearly defined and self-contained, it's easier to attribute costs and outcomes to a specific care team, enabling cleaner accountability under risk-based models.

Independent specialty: If the specialty is owned and operated independently, rather than by a health system, the independent specialists are more likely to transition to risk.

CMMI model: The factors above contribute to CMMI’s creation of models, and these models spur innovation.

Throughout this piece, I will highlight the importance of the first bullet, high-cost, because specialties that drive disproportionate spend create the clearest opportunity for value-based models to meaningfully reduce total cost of care.

If a statistic in this section does not have a source, it comes from this PDF 👇

William Blair Report on Specialty Value-Based Care.pdf

Kidney care

Kidney care is well-suited for risk-based models because it is a high cost and discrete condition. In these risk-based models, nephrologists deserve accountability for total cost of care due to the discrete nature of the condition, which policy makers and CMS have recognized.

First, let’s take a look at the cost. Medicare is spending over $50B per year on End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), which is roughly 1% of the overall federal budget. The average ESRD patient on dialysis costs roughly $100K per year, and there are roughly 800K ESRD patients (68% of whom are on dialysis).

Next, looking at the condition, Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) (the precursor to ESRD) affects roughly 15% of the population and is much more prevalent in Medicare (38%). Despite its prevalence, it is estimated that 90% of patients with CKD don’t know about their condition. Kidney disease is a discrete disease state where a specialized care model improves outcomes, reduces costs, and increases patient satisfaction. Deploying this specialized care model, nephrologists often are the quarterbacks of the condition as a relatively independent specialty (not employed by health systems). This dynamic is dissimilar to a condition like diabetes, where Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) manage the condition because of its prevalence, familiarity, and straightforward management protocols. In this care journey, nephrologists and care managers can positively impact care in a number of areas:

Slowing disease progression

Increasing optimal starts (beginning dialysis with a permanent vascular access already in place, rather than a catheter)

Reducing hospital admissions / readmissions

The movement from in-center to home dialysis

Due to the disease’s significant effect on the government’s budget and seniors’ health, policy makers have also stepped in to create change. The first wave of kidney care ‘hype’ started in 2021 with the 21st Century Cures Act and Kidney Care Choices (KCC). 21st Century Cures allowed all ESRD patients to be eligible for enrollment in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (the Social Security Amendments of 1972 allowed people with ESRD to enroll in Traditional Medicare). Additionally, the enhanced kidney-specific, CMMI model, Kidney Care Choices (KCC) gave nephrologists the option to take on risk, similar to how PCPs take on risk for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP).

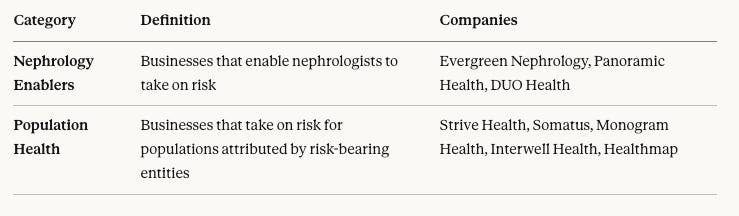

These policy tailwinds have created two primary business models in value-based kidney care: nephrology enablers and population health. KCC, the CMMI model, gave rise to many businesses focused on enabling nephrologists to take on risk, similar to what Aledade or other enablers do for PCPs (noticing a trend?). Most of these businesses create Kidney Care Entities (KCEs) (similar to ACOs) in Traditional Medicare. Businesses that only enable nephrologists are in the full-risk nephrology bucket. The population health bucket includes businesses that enter full-risk arrangements with payers, some of which also serve as enablers for nephrologists.

As one of the more advanced specialties in value-based specialty care, kidney care has received tons of funding from venture capital (and even newsletters). This funding and subsequent innovation has led to improved patient outcomes, fewer hospital admissions, lower costs, and an improved patient experience for thousands of individuals across the US.

Cardiology

The health and societal risks associated with cardiovascular diseases are significant. They are the number one cause of death around the world, killing 18M people annually and are responsible for 1 of every 3 deaths in the country. The financial burden is also substantial, representing the single largest source of spending among specialty conditions.

Digging into cost burdens associated with heart diseases, there is a significant opportunity for savings because of a high referral rate, their chronic nature, and cost-variation. About 15% of primary care visits related to cardiac conditions lead to a specialist referral, meaning that streamlined high-quality, low-cost referrals can have a significant impact. CMS reimbursement for outpatient treatments, like heart catheterizations, coronary interventions, and pacemaker implants, are a more cost-efficient method, often generating 50% to 60% of savings versus the acute-care setting. Cost-variation via over-utilization is also pervasive, as it is estimated that 35% of cardiac stress tests with imaging are clinically unwarranted. This cost-variation can lead to cost savings for risk-bearing entities and Medicare.

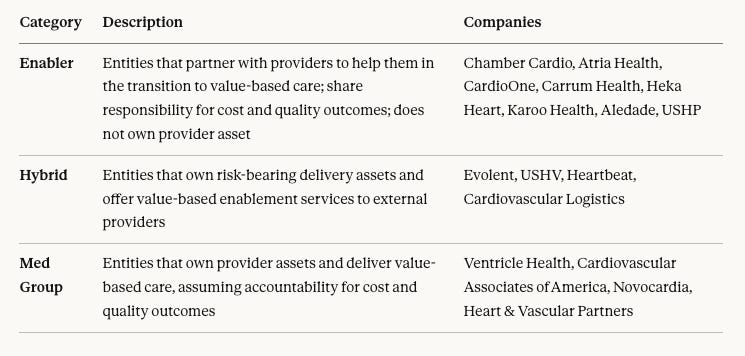

Making the transition to value more difficult, cardiology is a highly health-system-employed specialty. Even if a group is interested in moving to value, they might be constrained by the broader system’s fee-for-service (FFS) incentives. Typically, these ownership structures fall into 3 buckets across a spectrum from more aligned with a system to less aligned.

Health system owned cardiologist: Full-time employee of health system

Big cardiology groups: Affiliated with systems but independently owned

Independent cardiologists: Fewer and far between now

A second important consideration within cardiology is the deeply co-morbid nature of the condition, where it is often less clear which conditions should be handled by PCPs and which should be handled by specialists (cardiologists, nephrologists, etc.). In a world of complex risk attribution and a lack of clarity on a ‘true quarterback’ for the patient, value-based cardiology is faced with a true financial and clinical challenge. CMMI has recognized this complexity in neglecting to create a model with the cardiologist at the helm, although there have been programs which have taken a more preventative stance.

A third consideration is that many states have limited access to certain medical procedures in more convenient and cost-effective outpatient settings. Over 15 states still have not followed CMS in making Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (PCIs) available in lower cost, outpatient settings. In those states, regulatory barriers remain that prevent the expansion of these services outside of traditional hospital settings.

Behavioral Health

Despite the expansion of human lifespan and increase in global GDP, mental health has largely declined in the US. This imbalance exists, in part, because our current healthcare system is built to incentivize volume, over preventative treatments like those in behavioral health. However, public awareness, a shift in stigma, governmental support, and rapidly increasing employer demand have created opportunities for innovation, specifically in value-based care, where preventative, behavioral healthcare is being prioritized to reduce the total cost of care.

“Based on the 2022 prevalence of adolescent behavioral health conditions and symptoms, the ripple effects of the adolescent behavioral crisis are estimated at up to $185 billion in lifetime medical costs and $3 trillion in lifetime lost productivity and wages.”

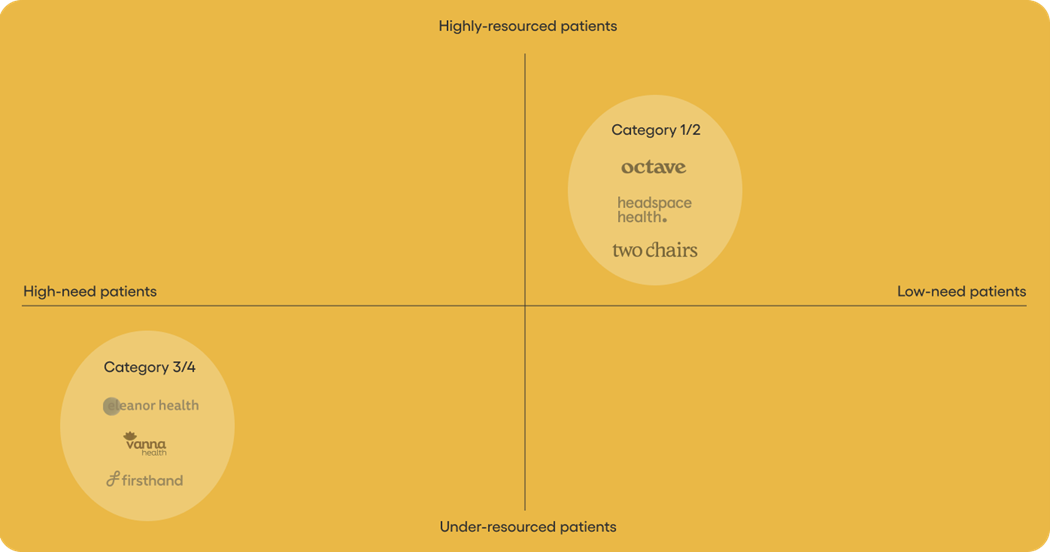

Behavioral healthcare is preventative healthcare for certain populations. High-quality, behavioral healthcare can not only reduce the severity of mental illness, but also reduce the cost of care associated with physical medical expenditures down the line. This correlation is only true within high-acuity populations, where patients tend to be under-resourced. For example, “a single patient with serious mental illness (SMI) is associated with ~$1,600 more in mental health spending and ~$2,600 more in medical spending compared to a patient with more common mental health disorders.”

Behavioral health organizations treating healthier and wealthier people are not well positioned to engage in value-based care (payment categories 3 & 4) because their mental healthcare does not drive significant downstream spend. These organizations are best positioned to engage in fee-for-service (categories 1 & 2) payment models. Organizations treating marginalized, under-resourced patients who tend to be higher-need (suffer from SMI / Substance Use Disorder (SUD)) are better set up to engage in value-based care because of the associated long-term reduction in total cost of care from preventative, behavioral healthcare.

There are four general categories for healthcare reimbursement: category 1: FFS, category 2: FFS with link to quality and value, category 3: shared saving models, and category 4: population-based-payments.

Companies in the bottom-left in the diagram below cater to this under-resourced patient population. As mentioned above, these patients tend to accrue higher medical costs over time, incentivizing health plans and providers to engage in shared savings models and population-based-payments. On the other hand, companies that cater to patients with less severe conditions and higher socioeconomic statuses generally fall into the first and second category, as they are not as costly to health plans.

Category 2: Quality Metrics

In some payment models within behavioral health, providers receive increased compensation for meeting specific quality metrics, and I’ll outline just a few of them below.

This approach is prevalent in treating low-acuity mental illnesses, where higher quality care may not necessarily correlate to reduced total cost of care. For instance, high-quality therapy for middle/upper-class college students with moderate depression is less likely to impact their future medical expenses, such as emergency room visits.

First, we’ll go through a few quality measures from HEDIS, a widely used set of standardized performance measures set by the NCQA (read more here):

Effectiveness of care: Antidepressant Medication Management

Access/Availability of care: Use of First-Line Psychosocial Care for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics (APP)

Utilization and risk-adjusted utilization: Mental Health Utilization (MPT)

Measures collected using electronic clinical data systems: Depression Screening and Follow-Up for Adolescents and Adults (DSF)

Provider organizations can also agree with health plans on more personalized quality metrics. Below are just a few examples that I’ve heard of but see more here:

Therapeutic alliance: This metric refers to the collaborative, trusting relationship between a therapist and client that fosters a supportive environment for personal growth and change in therapy. There are a variety of methods used to measure therapeutic alliance.

Appointment Availability: Provider organizations must have an appointment available within X number of days.

Second appointment retention: X% of patients must have a second appointment with providers.

Categories 3 & 4: Shared Savings & Population-based-payments

The profits generated from shared savings models and population-based-payments rely on the providers’ ability to significantly decrease the total cost of care over a given period.

The majority of these cost savings are related to physical conditions (i.e. someone has a manic episode and breaks their hip). Hence, these contracts are more common for companies treating patients whose mental illness puts them at risk for physical injury, ER admission, and other costly treatments.

As mentioned earlier, high-cost-high-need patients tend to be under-resourced and historically marginalized by the ‘system.’ This lack of trust has led to a lack of engagement with the healthcare system and preventative care. Providers like Cityblock and firsthand have taken creative, new ways of engaging this population, employing community-based peers to meet patients where they’re at and re-instill trust in this system.

This under-resourced patient population tends to be qualified for Medicaid plans where individuals stay on the same plan for longer periods of time, as compared to wealthier individuals on commercial plans. Wealthier individuals on commercial plans often switch carriers every few years due to their employer. Because of this longer duration of stay in Medicaid plans, categories 3 & 4 are more attractive because providers and plans are more likely to reap the savings years down the line.

Conclusion

The advent of value-based care in behavioral health is still in its early stages, and it remains unclear which organizations and populations can benefit from it. With the pioneering work from companies like Eleanor Health and Cityblock, health plans are beginning to see the value that can be created from high-quality behavioral healthcare. On the fee-for-service side, providers who are serving the walking-well are at odds with payers, as their treatments are not reducing long-term costs.

This same dynamic shows up across other specialties as well. Simply put, value-based care works best when providers are treating high-cost, high-acuity patients where better care reduces hospitalizations, procedures, and/or disease progression. In specialties like nephrology, cardiology, and behavioral health, organizations focused on complex patients can generate real savings, rather than relying on gamification of benchmarks / HCC coding, while those serving lower-acuity patients see limited financial upside. When care improves experience without materially changing long-term utilization, fee-for-service remains the more natural fit.